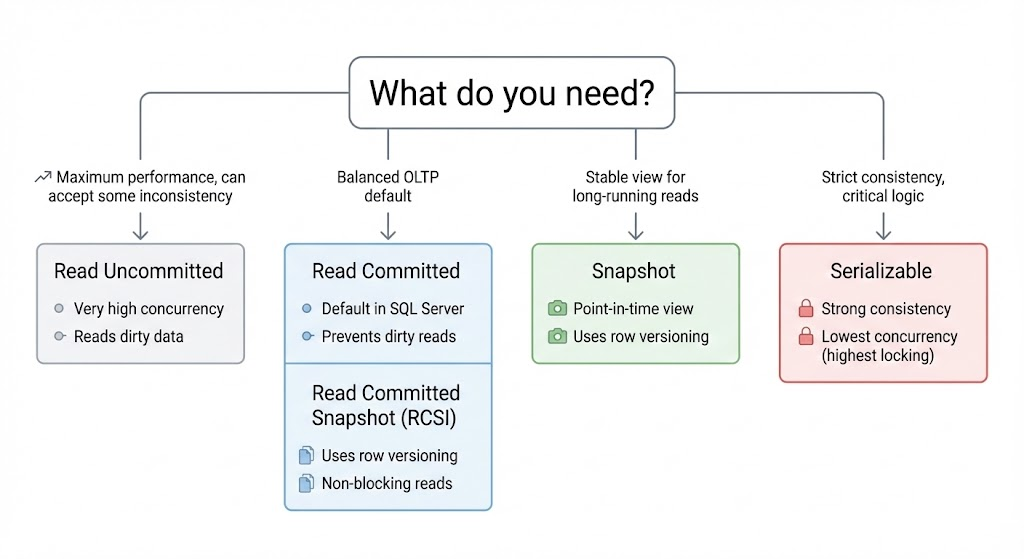

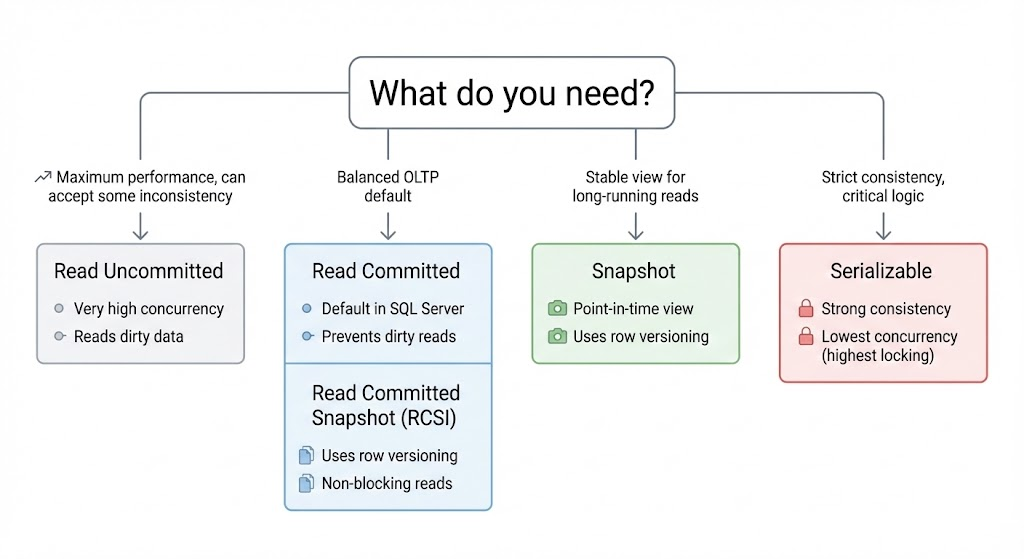

When multiple sessions read and update the same data at the same time, SQL Server uses transaction isolation levels to control how much they can see each other’s changes. The isolation level you choose is always a trade-off between data consistency and concurrency/performance.

SQL Server supports the following six isolation levels:

- Read Uncommitted

- Read Committed (default for SQL Server sessions)

- Repeatable Read

- Serializable

- Snapshot

- Read Committed Snapshot (RCSI)

In this article, we will:

- Review the typical read anomalies: dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, and phantom reads.

- Explain each isolation level in detail.

- Compare all levels in a single summary table.

1. Common Read Anomalies

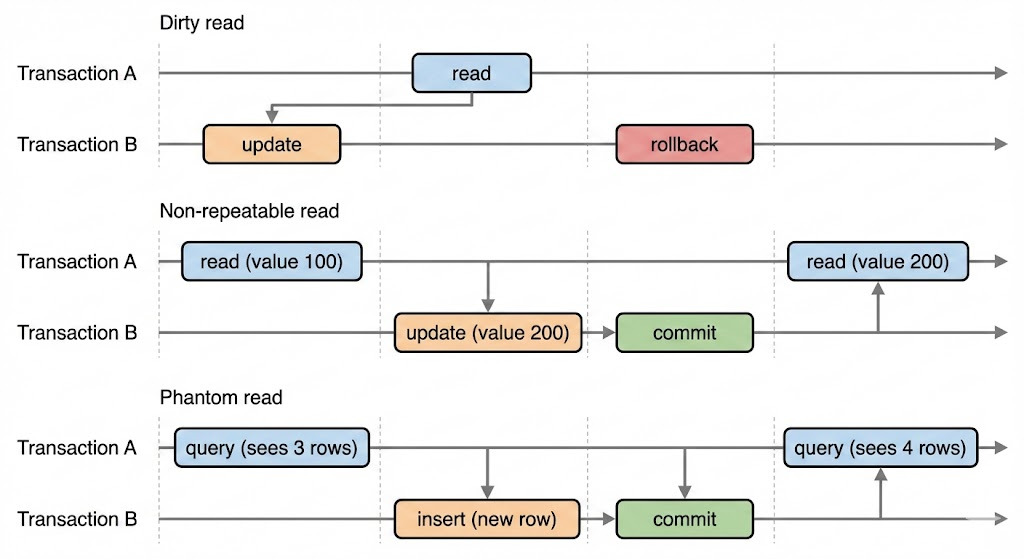

Before looking at each isolation level, it is helpful to define three classic read anomalies that isolation levels are designed to control.

1.1 Dirty read

A dirty read happens when a transaction reads data that has been modified by another transaction but not committed yet. If the modifying transaction later rolls back, the reader has seen a value that never truly existed in the committed data.

1.2 Non-repeatable read

A non-repeatable read occurs when a transaction reads the same row twice and gets different values because another transaction committed a change in between.

- Transaction A reads row R (value = 100).

- Transaction B updates row R to 200 and commits.

- Transaction A reads row R again and now sees 200.

Within a single logical unit of work, Transaction A cannot “repeat” its read.

1.3 Phantom read

A phantom read happens when a transaction re-runs a query that returns multiple rows (for example, a range query), and new rows appear or disappear because another transaction inserted or deleted rows in the meantime.

- Transaction A runs

SELECT * FROM Orders WHERE Amount > 1000;and gets 10 rows. - Transaction B inserts a new order with

Amount = 5000and commits. - Transaction A runs the same query again and now gets 11 rows.

Different isolation levels prevent or allow these anomalies in different ways.

2. Isolation Levels at a Glance

The following table summarizes how each isolation level behaves with respect to dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, phantom reads, and row versioning.

In the next sections, we will look at each isolation level in more detail and discuss when you might want to use it.

3. Read Uncommitted

Read Uncommitted is the loosest isolation level. It allows a session to read data that has been modified by other transactions but not committed yet. In T-SQL you can enable it like this:

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL READ UNCOMMITTED;

GO

In practice, many applications use the NOLOCK hint instead, which is equivalent for a single query:

SELECT *

FROM dbo.Orders WITH (NOLOCK);

3.1 Characteristics

- Prevents no anomalies: dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, and phantoms are all possible.

- Readers do not take shared locks and do not honor exclusive locks.

- Writers still take locks as usual; they are just ignored by these readers.

- Concurrency is very high, but the risk of reading incorrect data is also high.

3.2 When to use

- For diagnostic or ad-hoc queries where absolute accuracy is not critical.

- For reporting queries where small inconsistencies are acceptable and you prefer not to block OLTP activity.

You should avoid using Read Uncommitted or NOLOCK for business-critical logic that must not act on uncommitted or inconsistent data.

4. Read Committed (default)

Read Committed is the default isolation level in SQL Server. In its classic, locking-based form, it only allows reads of committed data.

With standard Read Committed:

- Reads take shared (

S) locks on rows or pages while accessing them. - Those locks are released when the statement finishes (not at transaction end).

- Writers take exclusive (

X) locks and block readers while they hold them.

4.1 Allowed and prevented anomalies

- Dirty reads: prevented (uncommitted changes are not visible).

- Non-repeatable reads: possible, because locks are released after each statement.

- Phantom reads: possible, because inserts/deletes can happen between statements.

4.2 When to use

- Good default for many OLTP workloads.

- Balanced trade-off between consistency and concurrency.

In systems with heavy read/write contention, you may want to consider Read Committed Snapshot (RCSI), which keeps the logical isolation level as “read committed” but uses row versioning instead of blocking readers.

5. Repeatable Read

Repeatable Read strengthens Read Committed by guaranteeing that rows you have already read cannot be changed by other transactions until you commit. You can enable it with:

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL REPEATABLE READ;

GO

5.1 Behavior

- When you read a row, SQL Server takes a shared (

S) lock and holds it until the transaction ends. - Other transactions cannot update or delete those rows while your transaction is active.

- However, other transactions can still insert new rows that match your query predicate.

5.2 Allowed and prevented anomalies

- Dirty reads: prevented.

- Non-repeatable reads: prevented (rows you read remain stable).

- Phantom reads: still possible because new rows can appear in the range.

5.3 Trade-offs and typical use

Because locks are held until the end of the transaction, blocking can increase significantly, especially for long-running transactions. Repeatable Read is mainly useful when you must ensure that the rows you have read will not change during the transaction, but you can tolerate new rows being inserted into the range.

6. Serializable

Serializable is the strictest isolation level. It makes concurrent transactions behave as if they were executed one after another, with no overlap.

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE;

GO

6.1 Behavior

- SQL Server takes and holds shared (

S) locks on all rows you read until the transaction ends. - It also takes range locks to prevent new rows from appearing in the accessed key ranges.

- Other transactions are blocked from inserting, updating, or deleting rows that would affect your query results.

6.2 Allowed and prevented anomalies

- Dirty reads: prevented.

- Non-repeatable reads: prevented.

- Phantom reads: prevented (thanks to range locks).

6.3 Trade-offs and typical use

- Provides the strongest guarantees but often has the lowest concurrency.

- Can cause significant blocking and deadlocks if used broadly in OLTP workloads.

- Typically reserved for critical operations that require strict correctness (for example, some financial calculations or complex integrity checks) and where higher cost is acceptable.

7. Snapshot Isolation

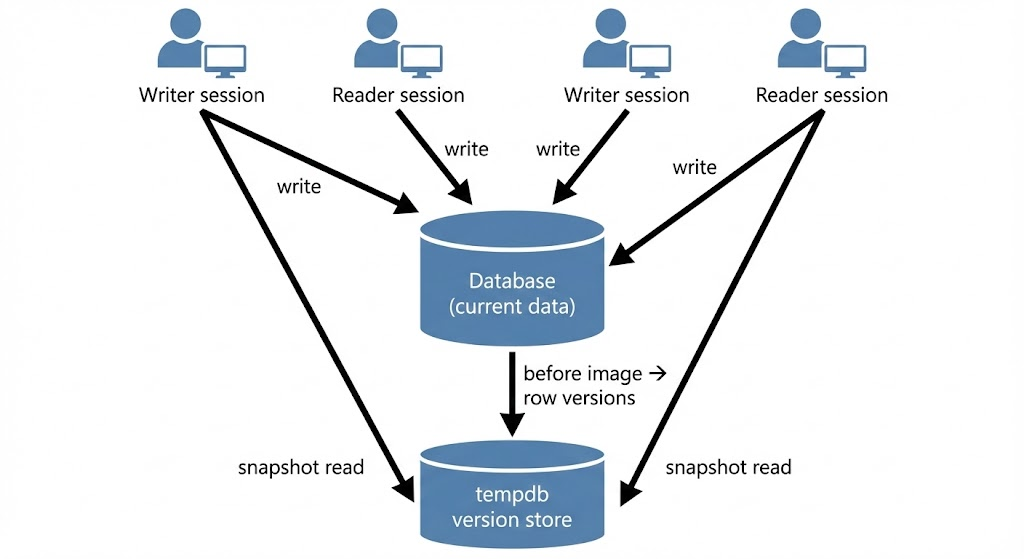

Snapshot isolation uses a row-versioning mechanism in tempdb to give each transaction a consistent snapshot of the data as of the moment the transaction started.

To use snapshot isolation, you must:

- Enable it at the database level:

ALTER DATABASE YourDatabase SET ALLOW_SNAPSHOT_ISOLATION ON; GO - Set the session’s isolation level:

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SNAPSHOT; GO

7.1 Behavior

- When rows are modified, their previous versions are copied to the version store in

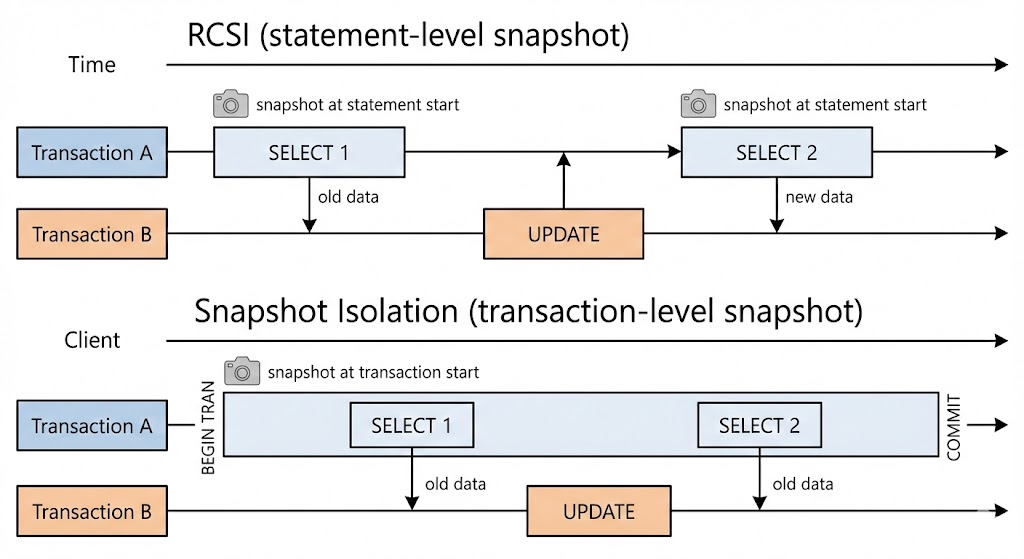

tempdb. - A transaction running under Snapshot reads from the version store, seeing data as it existed when the transaction started.

- Readers do not block writers, and writers do not block readers.

- If two concurrent transactions update the same row, one of them may receive an update conflict error at commit time.

7.2 Allowed and prevented anomalies

- Dirty reads: prevented (only committed versions are visible).

- Non-repeatable reads: prevented (the snapshot does not change during the transaction).

- Phantom reads: prevented within the transaction, because the snapshot is fixed at the transaction start.

7.3 Trade-offs and typical use

- Greatly improves concurrency between readers and writers.

- Shifts some costs to

tempdb(version store I/O and storage). - Useful for long-running read transactions that must see a stable view of the data without blocking writers.

8. Read Committed Snapshot (RCSI)

Read Committed Snapshot Isolation (RCSI) keeps the isolation level logically at “Read Committed” but implements it using row versioning instead of shared locks for reads. It is enabled at the database level:

ALTER DATABASE YourDatabase

SET READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT ON

WITH ROLLBACK IMMEDIATE;

GO

After this, sessions using the default isolation level (Read Committed) automatically use versioned reads instead of blocking writers.

8.1 Behavior

- Writers still generate row versions in

tempdbwhen changing data. - Readers under Read Committed use the latest committed version of each row at the time each statement starts.

- Readers do not take shared locks on data, so they do not block writers.

- Writers keep their usual exclusive locks while making changes.

- Unlike Snapshot isolation, RCSI does not read data as of the transaction start time; it takes a fresh snapshot at the start of each statement.

8.2 Allowed and prevented anomalies

- Dirty reads: prevented (only committed versions are visible).

- Non-repeatable reads: still possible because each statement sees a snapshot as of its own start time.

- Phantom reads: still possible for the same reason.

8.3 Trade-offs and typical use

- Often a great default for OLTP workloads that suffer from read/write blocking under classic Read Committed.

- Improves user experience by reducing timeouts and long waits on read queries.

- Like Snapshot, it increases dependency on

tempdband version store management.

9. Choosing an Isolation Level

There is no single “best” isolation level. The right choice depends on your workload, your tolerance for inconsistencies, and your performance goals. A common approach is:

- Use Read Committed Snapshot (RCSI) as a default for OLTP, if

tempdbcan handle the versioning load. - Use Snapshot for long-running logical transactions that need a stable view of the data.

- Use Serializable only for specific, critical operations that truly require strict correctness.

- Reserve Read Uncommitted for diagnostic/reporting queries where occasional inconsistencies are acceptable.

Understanding how each isolation level interacts with locking and row versioning is essential for designing an application that is both correct and scalable. By deliberately selecting the right isolation level per workload, you can balance consistency and concurrency instead of relying on the default behavior everywhere.