Optimized Locking in SQL Server 2025 and Azure SQL – How It Really Improves Concurrency

Traditional locking in SQL Server works, but it doesn’t always scale well. Large update transactions can hold thousands of row locks until the end of the transaction, consuming a lot of lock memory, causing lock escalation, and increasing the risk of blocking issues. The new optimized locking feature in SQL Server 2025 (17.x) and modern Azure SQL platforms is designed to address exactly these problems by changing how locks are acquired and held.

With optimized locking, the engine can:

- Reduce the number of row and page locks held during large DML operations

- Lower lock memory usage and the chance of lock escalation

- Increase concurrency by allowing more sessions to work on the same table at the same time

- Avoid some types of deadlocks that were common with heavy row locking

This article explains what optimized locking is, what does not change, what does change compared to traditional locking, where you can use it, how to enable it, and how its main components – transaction ID (TID) locks, lock after qualification (LAQ), and skip index locking (SIL) – impact real workloads.

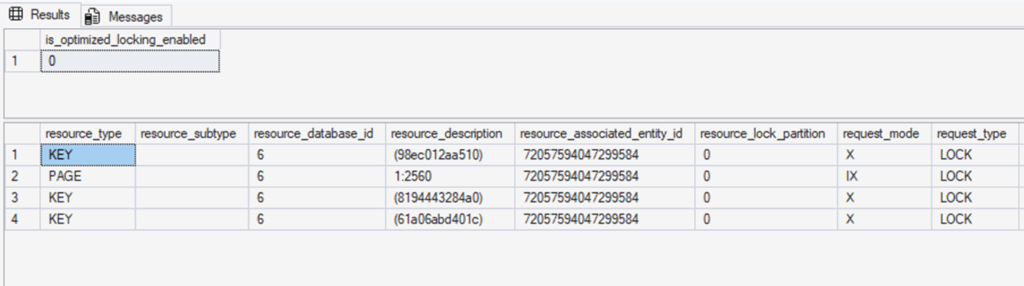

Traditional locking:

Optimized locking:

1. What Optimized Locking Does Not Change

First, it is important to be clear about what stays the same. Optimized locking does not turn SQL Server into a lock-free engine.

- SQL Server is still a lock-based relational database engine.

- If two sessions try to update the same row at the same time, one of them will still wait, just like before.

- Isolation guarantees are preserved: SQL Server still prevents dirty reads, lost updates, and other anomalies, depending on the isolation level.

In other words, write–write conflicts are still real conflicts. Optimized locking does not magically remove contention. Instead, it changes how many locks exist, how long they live, and where contention tends to appear.

2. What Actually Changes Compared to Traditional Locking

You can think about locking behavior along three axes:

- How many locks are held at the same time

- How long each lock is held

- Which operations are blocked by those locks

Optimized locking changes all three.

2.1 Before: many long-lived row locks

Consider a typical large update:

BEGIN TRAN;

UPDATE Sales

SET Amount = Amount * 1.1

WHERE OrderDate >= '2025-01-01';

-- COMMIT is delayed

In the traditional model (simplified):

- The engine scans the index or heap.

- For each candidate row, it acquires a

U(update) lock, and if the row matches the predicate, it converts that to anX(exclusive) lock. - Those

Xrow locks are held until the transaction commits.

If 10,000 rows qualify, the transaction may hold thousands of row and page locks simultaneously until the end of the transaction. That leads to:

- High lock memory consumption

- Higher risk of lock escalation to page or table level

- More blocking, because other sessions are likely to hit one of these long-lived locks somewhere on the table

This blocking also affects rows that are never actually updated in the final result, simply because they were touched during the scan and held under U / X locks.

2.2 After: short-lived row locks + a single long-lived TID lock

With optimized locking (TID + LAQ):

- The engine still acquires

Xrow locks when it needs to modify a row, but those locks are short-lived and are released soon after the row is changed. - Instead of keeping thousands of row locks until commit, the transaction keeps a single long-lived TID lock that represents “the set of rows touched by this transaction”.

- With LAQ and RCSI, predicate evaluation can happen on committed row versions without holding row locks, and locks are only taken on rows that actually qualify for modification.

The practical effect is that, for the same 10,000-row update:

- The number of concurrent row locks is closer to “the number of rows currently being processed” rather than “all rows touched so far”.

- Long-lived row locks are replaced by a small number of TID (XACT) locks.

- Other sessions are less likely to be blocked by random row locks scattered across the table; they mostly wait only when they truly conflict on the same rows.

This is not just a memory optimization. It also reduces the probability of lock escalation, changes blocking patterns, and can lower the chance of deadlocks caused by long-lasting U/X row locks on large data sets.

2.3 How it feels from an application perspective

For a single-row update, there is little difference:

- Before: one row is locked and then released at commit.

- After: one row is locked and then released (plus a TID lock), which feels almost the same.

But for large, long-running transactions under concurrent load:

- The table may feel “sticky” because long-lived row/page locks are scattered everywhere.

- With optimized locking, other sessions can more easily update or read rows that are not actually in conflict with the big transaction, because most row locks are short-lived and many predicates can be evaluated lock-free.

The bottom line is:

- Locks still exist and conflicts still happen.

- However, where locks are held, how many exist, and how long they live are optimized so that fewer sessions are blocked “by accident”.

2.4 A concrete before/after example

Let’s look at a simple, reproducible scenario that shows how blocking patterns change with optimized locking.

We will:

- Create a demo table

dbo.T1and insert rows withidvalues from 1 to 100,000. - In Session 1, start a long-running transaction that updates rows where

id <= 90,000. - In Session 2, try to update rows where

id >= 90,001.

Without optimized locking, the first transaction holds many row/page locks for a long time. In many environments this leads to lock escalation to a table lock, so the second update can be blocked even though it targets a different range of IDs. With optimized locking, the first transaction mainly holds a TID lock for the rows it has touched, row locks are released quickly, and the second transaction can often update its own range without lock conflicts.

2.4.1 Demo setup

The following script creates a test database and table, and populates 100,000 rows. Run this once to prepare the environment.

-- Create a dedicated demo database (optional)

CREATE DATABASE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

USE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

-- Simple demo table

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.T1;

GO

CREATE TABLE dbo.T1

(

id int NOT NULL CONSTRAINT PK_T1 PRIMARY KEY,

value int NOT NULL,

filler char(200) NULL -- make rows a bit larger to spread across pages

);

-- Insert 100,000 rows (id = 1..100000)

;WITH Numbers AS

(

SELECT 1 AS n

UNION ALL

SELECT n + 1

FROM Numbers

WHERE n < 100000

)

INSERT INTO dbo.T1 (id, value, filler)

SELECT n, 0, REPLICATE('X', 200)

FROM Numbers

OPTION (MAXRECURSION 0);

SELECT COUNT(*) AS row_count FROM dbo.T1; -- should be 100000

2.4.2 Behavior without optimized locking

This approximates the traditional locking behavior (for example, SQL Server 2019 and earlier, or SQL Server 2025 with optimized locking disabled). If you are on SQL Server 2025, you can explicitly turn optimized locking off:

USE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

-- Only on SQL Server 2025:

ALTER DATABASE OptimizedLockingDemo

SET OPTIMIZED_LOCKING = OFF WITH ROLLBACK IMMEDIATE;

GO

Now open two separate sessions in SSMS / Azure Data Studio.

Session 1 – long-running update on id <= 90,000

USE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

BEGIN TRAN;

UPDATE dbo.T1

SET value = value + 1

WHERE id <= 90000;

-- Keep the transaction open on purpose

WAITFOR DELAY '00:05:00'; -- simulate a long-running business process

ROLLBACK TRAN;

Session 2 – try to update rows where id >= 90,001

USE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

BEGIN TRAN;

UPDATE dbo.T1

SET value = value + 10

WHERE id >= 90001;

ROLLBACK TRAN;

In the traditional locking model, Session 1 may end up holding thousands of row/page locks and, once internal thresholds are exceeded, SQL Server can escalate to a table-level lock. When that happens, Session 2 is blocked until Session 1 finishes, even though it is logically updating a different range of IDs.

If you do not observe blocking on your system, try increasing the number of rows (for example, to 500,000 or 1,000,000) or widening the range in the first update so that more locks are taken and escalation is more likely.

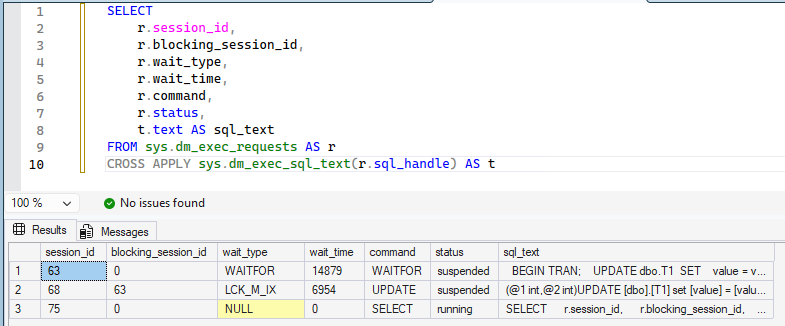

While Session 2 is waiting, you can observe the blocking from a third window:

SELECT

r.session_id,

r.blocking_session_id,

r.wait_type,

r.wait_time,

r.command,

r.status,

t.text AS sql_text

FROM sys.dm_exec_requests AS r

CROSS APPLY sys.dm_exec_sql_text(r.sql_handle) AS t;

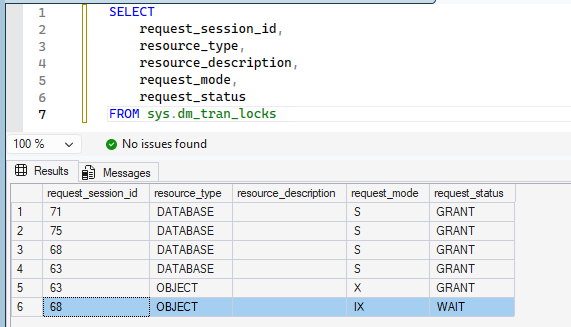

You can also inspect the locks that are currently held:

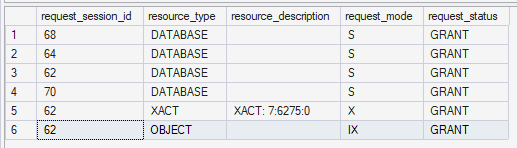

SELECT

request_session_id,

resource_type,

resource_description,

request_mode,

request_status

FROM sys.dm_tran_locks;

You should see that Session 2 is waiting on a lock-related wait type such as LCK_M_X or LCK_M_IX, blocked by Session 1, and that Session 1 is holding many row/page locks (or even a table lock if escalation has occurred).

2.4.3 Behavior with optimized locking enabled

Now repeat the same experiment with optimized locking turned on. On SQL Server 2025, make sure ADR and RCSI are enabled first, then enable optimized locking:

USE master;

GO

ALTER DATABASE OptimizedLockingDemo

SET ACCELERATED_DATABASE_RECOVERY = ON

WITH ROLLBACK IMMEDIATE;

GO

ALTER DATABASE OptimizedLockingDemo

SET READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT ON

WITH ROLLBACK IMMEDIATE;

GO

ALTER DATABASE OptimizedLockingDemo

SET ALLOW_SNAPSHOT_ISOLATION ON;

GO

ALTER DATABASE OptimizedLockingDemo

SET OPTIMIZED_LOCKING = ON

WITH ROLLBACK IMMEDIATE;

GO

USE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

SELECT

name,

is_accelerated_database_recovery_on,

is_read_committed_snapshot_on,

is_optimized_locking_on

FROM sys.databases

WHERE name = 'OptimizedLockingDemo';

Then, run the same two-session test again.

Session 1 – long-running update on id <= 90,000 (with optimized locking)

USE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

BEGIN TRAN;

UPDATE dbo.T1

SET value = value + 1

WHERE id <= 90000;

WAITFOR DELAY '00:05:00';

ROLLBACK TRAN;

In this session, SQL Server does not take an X (exclusive) lock on the table itself. As the lock information shows, it holds an IX (intent exclusive) lock on the table and an XACT lock for the transaction that covers the updated rows, rather than thousands of long-lived row locks.

Session 2 – update rows where id >= 90,001 (with optimized locking)

USE OptimizedLockingDemo;

GO

BEGIN TRAN;

UPDATE dbo.T1

SET value = value + 10

WHERE id >= 90001;

ROLLBACK TRAN;

With optimized locking and RCSI enabled, the first transaction holds a TID lock that protects the rows it has modified (id <= 90,000), and row/page locks are released much more quickly. The predicate for the second statement (id >= 90,001) is evaluated based on committed row versions without taking row locks up front, and only the rows that qualify are briefly locked while they are updated.

In many cases, this means the second update can complete without being blocked by the first, as long as it does not try to change the same rows. Because row locks are short-lived and fewer locks are held concurrently, SQL Server is less likely to escalate to a table lock in this scenario.

You can again monitor sys.dm_exec_requests and sys.dm_tran_locks to confirm that:

- Session 1 mainly holds an

XACTTID lock instead of thousands of long-lived row locks. - Session 2 is not stuck waiting on

LCK_M_X/LCK_M_IXfor rows it does not actually conflict with.

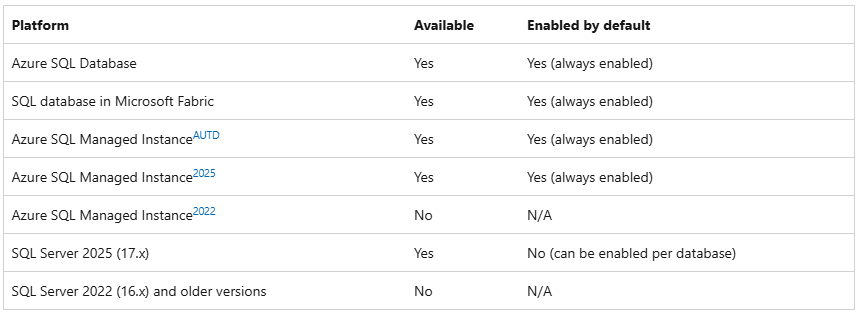

3. Where Is Optimized Locking Available?

At the time of writing, optimized locking is available on the following platforms:

- Azure SQL Database – available and always enabled

- Microsoft Fabric SQL database – available and always enabled

- Azure SQL Managed Instance (AUTD / 2025) – available and always enabled

- SQL Server 2025 (17.x) – available, but disabled by default per database

- SQL Server 2022 (16.x) and earlier – not available

On Azure SQL Database and Microsoft Fabric SQL, you benefit from optimized locking out of the box. On SQL Server 2025, you choose which databases should use it.

Reference: Optimized Locking – SQL Server | Microsoft Learn

4. Prerequisites and How to Enable Optimized Locking

Optimized locking is not a completely isolated feature. It is built on top of other database capabilities, so you must meet some prerequisites.

4.1 ADR is required

Accelerated Database Recovery (ADR) must be enabled on the database before you can enable optimized locking. Conversely, if optimized locking is enabled, you cannot disable ADR until you turn optimized locking off.

4.2 RCSI is strongly recommended

To get the full benefit, especially from the LAQ component, you should enable READ COMMITTED SNAPSHOT ISOLATION (RCSI) for the database. LAQ only works when RCSI is turned on because it relies on row versioning and the “latest committed version” of a row.

4.3 Enabling optimized locking on SQL Server 2025

On SQL Server 2025, you typically enable the following in order: ADR, RCSI, then optimized locking.

Step 1: Enable ADR (if not already enabled)

ALTER DATABASE YourDatabase

SET ACCELERATED_DATABASE_RECOVERY = ON;

GO

Step 2: Enable RCSI

ALTER DATABASE YourDatabase

SET READ_COMMITTED_SNAPSHOT ON

WITH ROLLBACK IMMEDIATE;

GO

-- Optional but often recommended together with RCSI

ALTER DATABASE YourDatabase

SET ALLOW_SNAPSHOT_ISOLATION ON;

GO

Step 3: Enable optimized locking

ALTER DATABASE YourDatabase

SET OPTIMIZED_LOCKING = ON; -- or OFF

GO

Before enabling it, it is a good idea to confirm your current settings:

SELECT database_id,

name,

is_accelerated_database_recovery_on,

is_read_committed_snapshot_on,

is_optimized_locking_on

FROM sys.databases

WHERE name = DB_NAME();

You can also query a single property for the current database:

SELECT DATABASEPROPERTYEX(DB_NAME(), 'IsOptimizedLockingOn')

AS is_optimized_locking_enabled;

The result is 1 when optimized locking is enabled, 0 when disabled, and NULL when the feature is not available on that platform.

5. Transaction ID (TID) Locking in Practice

When row versioning isolation or ADR is enabled, each row internally stores a transaction ID (TID) that identifies the last transaction that changed it. Optimized locking builds on that metadata: instead of keeping many long-lived row locks, the engine can lock the transaction that touched those rows.

Conceptually, it looks like this:

- A write transaction holds an

Xlock on a TID resource that represents the work it has done. - Other transactions that need a consistent view of those rows can take

Slocks on the same TID resource. - Row and page locks are still used to physically update data, but they are released immediately after each row is changed.

So a transaction that modifies many rows keeps only one long-lived TID lock instead of thousands of long-lived row locks. This reduces lock memory usage and makes lock escalation much less likely.

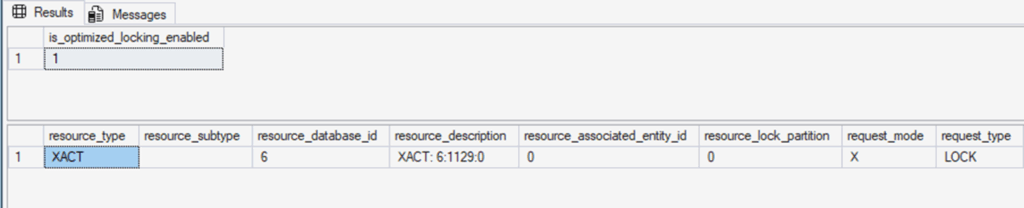

5.1 Observing TID locking with sys.dm_tran_locks

The following example shows how you might observe TID locking behavior:

/* Check if optimized locking is enabled */

SELECT DATABASEPROPERTYEX(DB_NAME(), 'IsOptimizedLockingOn')

AS is_optimized_locking_enabled;

CREATE TABLE dbo.T0

(

a int PRIMARY KEY,

b int NULL

);

INSERT INTO dbo.T0 VALUES (1,10),(2,20),(3,30);

GO

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE dbo.T0

SET b = b + 10;

SELECT *

FROM sys.dm_tran_locks

WHERE request_session_id = @@SPID

AND resource_type IN ('PAGE','RID','KEY','XACT');

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

GO

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.T0;

With optimized locking enabled, you should see a single XACT lock for the transaction resource plus a small number of short-lived row/page locks, instead of many row-level KEY locks being held for the entire transaction.

6. Lock After Qualification (LAQ) – “Lock Later, Not Sooner”

Lock After Qualification (LAQ) changes when row locks are acquired for INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE when RCSI is enabled.

6.1 Traditional behavior

Without LAQ, an UPDATE typically follows this pattern:

- Scan rows and acquire a

U(update) lock on each candidate row. - If the row matches the predicate, convert the

Ulock to anX(exclusive) lock. - Hold the

Xlock until the transaction commits.

This means that even if two sessions update different rows, they can still block each other just because they are scanning the same table and holding U/X locks for a long time.

6.2 Behavior with LAQ

With LAQ and RCSI, SQL Server can:

- Read the latest committed versions of rows without taking row locks.

- Evaluate the predicate against those versions.

- Only for rows that qualify, acquire a short-lived

Xlock to perform the update. - Release the row lock as soon as the row is updated.

As a result, concurrent transactions that update different rows are much less likely to block each other during the scan phase; they only contend when they really touch the same row.

A simple two-session scenario looks like this:

-- Session 1

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE dbo.T1

SET value = value + 10

WHERE id = 1;

-- COMMIT later

-- Session 2

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE dbo.T1

SET value = value + 10

WHERE id = 2;

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

-- Finally, Session 1 commits

COMMIT TRANSACTION;

Without LAQ, Session 2 can be blocked because Session 1 already holds locks on the page or row. With LAQ, the predicate for id = 2 can often be evaluated without taking unnecessary locks, so Session 2 can complete even while Session 1 is still open.

Internally, LAQ can fall back to traditional locking for statements that cannot safely be retried (for example, some statements with variables or OUTPUT clauses). In those situations, you can simply assume that the statement behaves like the classic locking model; no special tuning is usually required.

7. Skip Index Locking (SIL) – Fewer Index Locks When You Can

The third component, Skip Index Locking (SIL), further reduces the number of index locks when no queries require strict repeatable reads at the row level.

Roughly speaking, SIL can be applied when:

- Optimized locking and RCSI are enabled, and

- There are no concurrent queries running under

SERIALIZABLEor using strong lock hints that require long-lived row locks.

Under those conditions, SQL Server can skip some index-level locks for certain operations and rely mainly on page latches plus TID locks to maintain consistency, while still preserving ACID semantics.

Typical cases where SIL is used include:

- INSERT into heaps – the engine can often skip

IXpage locks. - UPDATE on clustered indexes, nonclustered indexes, and heaps – in many situations, it can avoid spreading

Xrow locks across the index structures.

On the other hand, SIL is not applied in scenarios such as:

DELETEstatements- Updates involving heap rows with forwarding pointers (either existing or newly created)

- Updates to rows with LOB columns (

varchar(max),nvarchar(max),varbinary(max),json, etc.) - Rows on pages that are being split by the same transaction

You don’t need to memorize every implementation rule. The key idea is that SQL Server still takes traditional locks when strict row-level consistency is required, and otherwise tries to minimize index locks as much as it safely can.

8. Summary

- Optimized locking reduces the number and lifetime of row and page locks taken by DML statements, lowering lock memory usage and the risk of lock escalation.

- It is built on top of transaction ID (TID) locking and lock after qualification (LAQ), with skip index locking (SIL) providing further lock reductions when row-locking queries are not present.

- ADR is required, and RCSI is strongly recommended to unlock the full benefits of optimized locking.

- On Azure SQL and Fabric SQL databases, optimized locking is always enabled; on SQL Server 2025, you enable it per database with

ALTER DATABASE ... SET OPTIMIZED_LOCKING = ON. - Write–write conflicts still exist, but the number, duration, and placement of locks are optimized so that fewer sessions are blocked unnecessarily.

- By understanding how TID, LAQ, and SIL work together, you can safely adopt optimized locking and gain higher concurrency with fewer lock-related incidents.

If you are planning to adopt SQL Server 2025 or are already using Azure SQL, optimized locking is one of the most impactful features you can take advantage of to improve write-heavy workloads with minimal code changes.