How to manage pages in SQL Server?

How are pages actually used in SQL Server? In this article, I summarize how SQL Server stores data in pages so you can understand the overall mechanism.

Basics of Pages and Extents

On disk, SQL Server data is managed in units called pages and extents. The key point is that SQL Server I/O is performed at the page level.

- Page: The basic unit (8KB)

- Extent: A group of 8 pages (64KB). The basic unit for space management

Inside a Page (Data Page Structure)

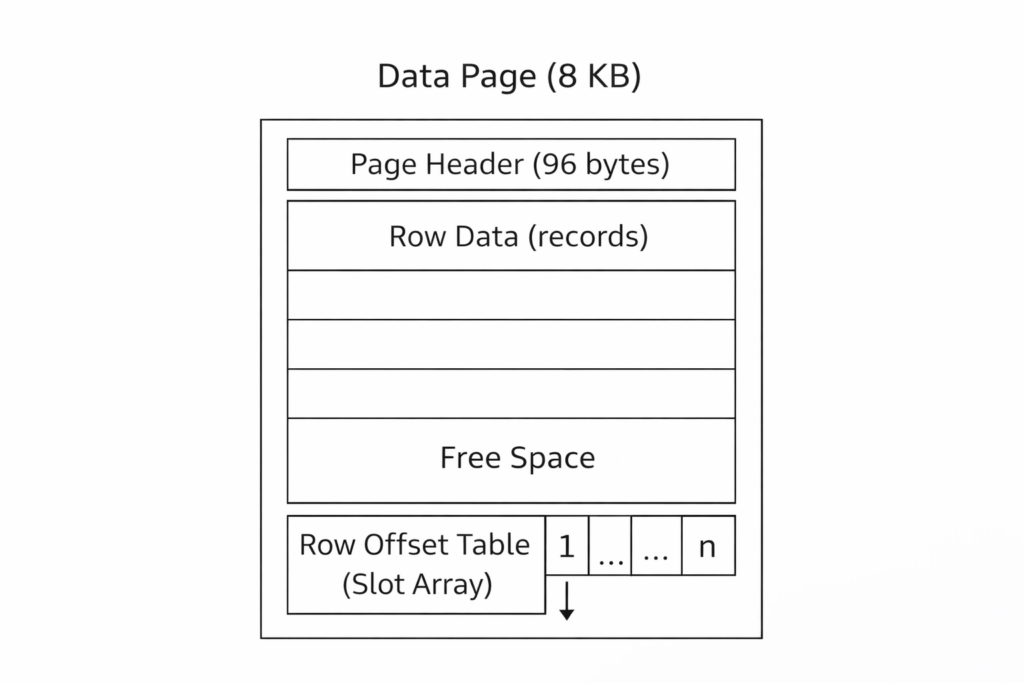

A page starts with a page header, followed by data rows. At the end of the page, there is a “row offset table (slot array)” that stores the offset (starting position) of each row. This allows SQL Server to quickly locate rows on the page.

Rows cannot span pages. Therefore, the maximum size that can be stored in a page as a single row (data + overhead) is 8,060 bytes.

The Concept of Three Data Areas

SQL Server maintains sets of pages (allocation units) for each table (more precisely, each partition), depending on the purpose. The three common allocation units are:

- IN_ROW_DATA: Normal row data (stored here by default)

- ROW_OVERFLOW_DATA: Space used when the row size exceeds 8,060 bytes and variable-length columns are moved out

- LOB_DATA: Space for large objects (for example, xml, varchar(max), varbinary(max), etc.)

IN_ROW_DATA (Normal Row Data)

In general, normal row data is stored in IN_ROW_DATA data pages. A page can contain multiple rows, but a row itself cannot span pages.

ROW_OVERFLOW_DATA (Move-Out When a Row Is Too Large)

When the total size of fixed-length and variable-length columns exceeds 8,060 bytes, SQL Server dynamically moves one or more variable-length columns to ROW_OVERFLOW_DATA pages, starting with the largest variable-length columns. After the move, a 24-byte pointer remains on the IN_ROW_DATA side. If the row size becomes smaller, the data may be moved back to the original data page.

LOB_DATA (Storing Large Data)

LOB_DATA is used to store large objects (for example, xml, varchar(max), varbinary(max), etc.). Depending on the table definition and stored data, LOB_DATA may be used.

What Do Allocation Pages (GAM / SGAM / PFS / IAM, etc.) Do?

SQL Server has “allocation pages” that manage the allocation status of pages and extents. Common examples include:

- GAM: Tracks whether an extent is allocated

- SGAM: Tracks mixed extents that still have free pages

- PFS: Tracks each page’s allocation status and free-space category

- IAM: Tracks which extents are used by a specific allocation unit

- DCM / BCM: Tracks changed extents for backup purposes

GAM and SGAM (Extent-Level Management)

GAM tracks whether an extent is free or already allocated. SGAM tracks extents that are being used as mixed extents and still have free pages. With these pages, SQL Server can efficiently allocate new uniform extents or find free pages in mixed extents when needed.

PFS (Page-Level Free Space Management)

PFS tracks whether a page is allocated and how much free space it has (by category). SQL Server uses this information to find a page with enough free space when inserting new rows into heaps and LOB-related pages.

IAM (Which Extents an Object Uses)

IAM tracks which extents in the data file are used by a specific allocation unit (IN_ROW_DATA / LOB_DATA / ROW_OVERFLOW_DATA). If an allocation unit spans multiple files or ranges, multiple IAM pages are required and they are linked as an IAM chain.

Transaction Log (.ldf) Internal Management (VLF / Log Block / LSN)

The Page/Extent concepts described so far are units used to store data in data files (.mdf / .ndf). In contrast, SQL Server also records changes in the transaction log (.ldf) so it can safely recover updates. Because the log has a different purpose from data files, its internal management is also different.

The Log Is a Sequence of Log Records (Managed by LSN)

Logically, the transaction log is treated as a string of log records that move forward in one direction. Each log record is assigned an LSN (Log Sequence Number), and LSNs are written in increasing order.

The basic structure of an LSN is expressed as [VLF ID:Log Block ID:Log Record ID]. In other words, the log has a hierarchy of “VLF”, “log block”, and “log record”.

Physically, the Log Is Split into VLFs and Wraps Around When Needed

The physical log file (.ldf) is internally divided into multiple VLFs (Virtual Log Files). Log records are appended to the “end of the logical log”, and when the end reaches the physical end of the file, writing continues by wrapping around to the beginning.

The key concept here is the “active portion of the log.” While older log records are still needed for recovery, the VLFs that contain them cannot be reused. Once log space is no longer needed, it is marked reusable through “log truncation” and is reused at the VLF level.

Typical cases where log truncation occurs include: after a checkpoint in the SIMPLE recovery model, and (in the FULL / BULK_LOGGED recovery models) when a log backup has occurred and a checkpoint has occurred since the previous backup.

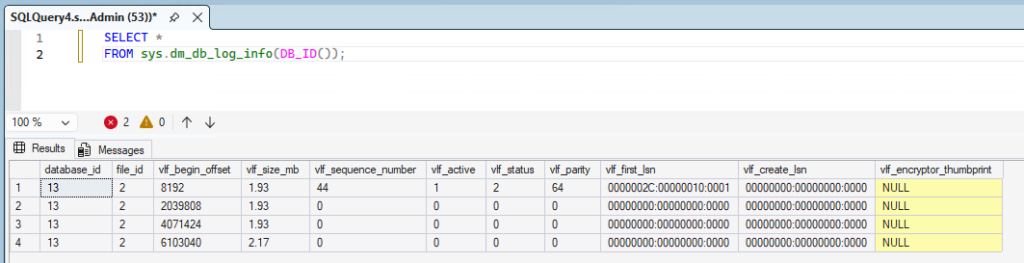

You can check VLF status using sys.dm_db_log_info (each row represents a VLF, and you can review columns such as active and first_lsn).

-- Check VLF status

SELECT *

FROM sys.dm_db_log_info(DB_ID());

A Log Block Is the I/O Unit for Writing the Log

Each VLF consists of one or more “log blocks.” A log block is variable in size, is a multiple of 512 bytes (up to 60KB), and is treated as the basic I/O unit when writing the log to disk. Multiple log records are packed into a log block.